The 2025 Federal Government Shutdown and Its Impact on Nutrition Assistance Programs: A Case Study of SNAP, EBT, and WIC

Research for post done by Public Health Intern Nicole Previde

Introduction: Defining SNAP, EBT & WIC

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest federally funded food assistance initiative in the United States, administered by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) under the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). SNAP provides essential benefits to low-income individuals, families, seniors, and people with disabilities who struggle to afford nutritious foods. Its primary goal is to “increase food security and reduce hunger in partnership with cooperating organizations by providing children and low-income people access to food, a healthy diet, and nutrition education in a manner that supports American agriculture and inspires public confidence.”

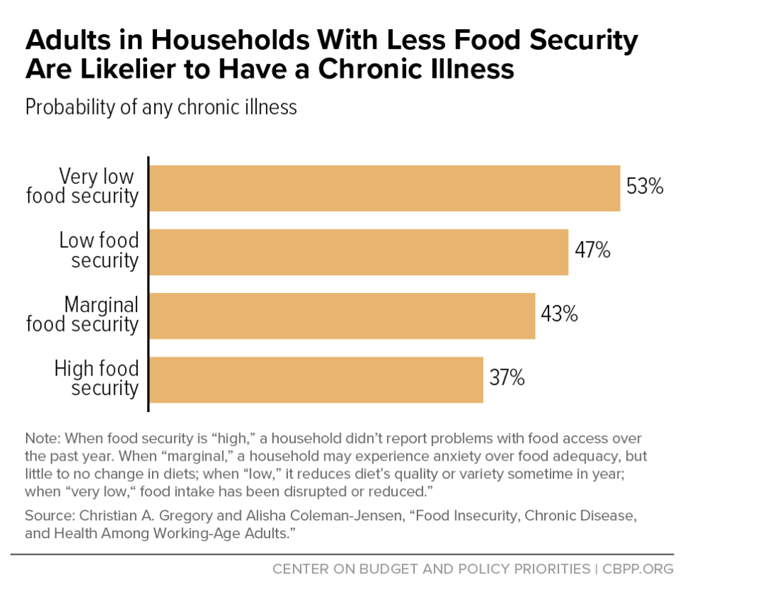

In practice, this means ensuring that families are not forced to choose between rent, healthcare and food, a tradeoff that contributes significantly to social determinants of health. Research consistently shows that social and economic inequalities drive major health disparities: people in poverty live shorter lives and face higher rates of chronic disease. Much of this gap stems from poor nutrition, as limited income and food access lead to diets low in essential nutrients and high in processed foods. These inequities begin early, persist across generations, and are worsened by limited access to affordable, healthy food and quality healthcare. Because poor nutrition is linked to chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (see Figure 1), SNAP functions not only as a hunger relief program but also as a preventive health intervention that targets the upstream causes of poor health outcomes.

To facilitate access, SNAP introduced the Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) system, which operates like a prepaid debit card. Each month, beneficiaries receive an automatic deposit into their EBT account, which can be used at participating grocery stores, farmers’ markets, and retailers to purchase eligible food items such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, grains, and proteins. This system modernized food assistance delivery by reducing stigma, increasing accessibility, and improving oversight of benefit distribution.

In addition to SNAP, the USDA administers several other nutrition programs, one of the most impactful being the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). WIC provides nutritious foods, breastfeeding support, health screenings, and nutrition education to pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk. Unlike SNAP, which is a broad food assistance program, WIC is targeted toward maternal and early childhood health, addressing the critical developmental period when adequate nutrition has long-term implications for growth, cognitive function, and overall well-being.

WIC participants receive vouchers that can be used to purchase specific nutrient-rich foods, such as milk, eggs, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and infant formula, designed to supplement their diets rather than fully cover food costs. The program also connects families to local health departments, community clinics, and social services, reinforcing a holistic approach to family health.

Together, SNAP, EBT, and WIC represent a vital safety net that supports millions of Americans each month, helping to reduce hunger while advancing health equity and nutritional security nationwide.

Historical Background

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) traces its origins to the Food Stamp Program, which began as a pilot initiative under President John F. Kennedy in 1961. The program emerged from two intersecting national issues: surplus agricultural products going to waste and widespread hunger among low-income Americans. Its purpose was to redirect excess farm goods toward feeding the poor, aligning agricultural stability with humanitarian need.

During its first fiscal year, the pilot program cost approximately $13 million and served around 140,000 participants across several states. Encouraged by its initial success, the program was written into permanent law in 1964. However, state participation was voluntary, and many states initially opted out due to administrative challenges and political opposition. By the late 1960s, despite federal funding reaching $30 million, fewer than 500,000 individuals were enrolled.

That changed dramatically by 1969, when rising public awareness, advocacy from anti-hunger organizations, and growing recognition of poverty as a national crisis led to a surge in participation, reaching nearly 3 million beneficiaries. In subsequent years, federal amendments required all states to participate, greatly expanding access and standardizing eligibility criteria.

However, the 1970s brought controversy and reform. Reports of program abuse, particularly by college students and non-working adults, fueled political backlash. The Food Stamp Act of 1977 introduced many reforms: tightening eligibility requirements, simplifying administration, and improving program integrity. Although participation briefly declined, the program continued to evolve as an essential component of the national safety net.

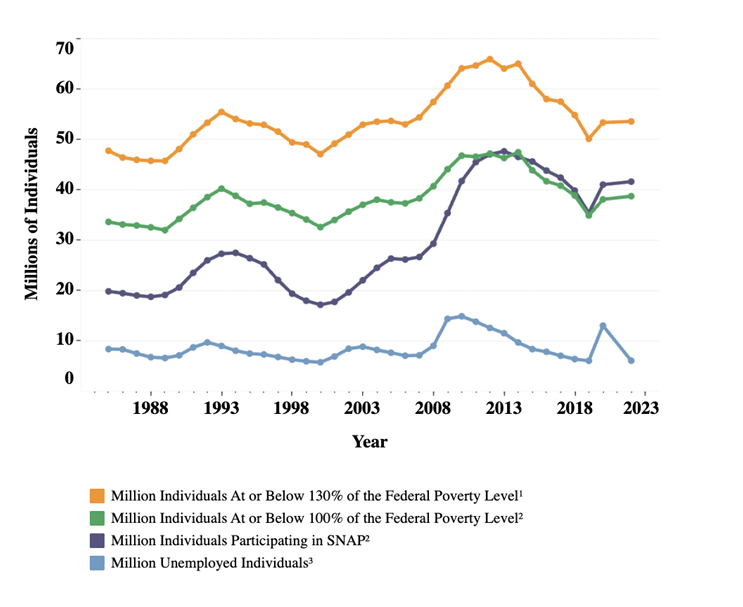

Over the following decades, SNAP expanded in response to economic downturns, including the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which sharply increased food insecurity. By Fiscal Year 2022, the program served over 40 million Americans, reflecting its ongoing role as a stabilizing force during times of economic hardship and a critical tool in reducing hunger nationwide.

Parallel to SNAP’s evolution, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was established in 1972 as a targeted response to maternal and child malnutrition. Initially launched as a pilot project under the Child Nutrition Act, WIC rapidly expanded, operating in 45 states by 1974, and was made permanent by Congress in 1975. Early program evaluations demonstrated marked improvements in birth outcomes, child growth, and nutritional status, prompting expansions in eligibility and services.

By the late 1970s, eligibility had broadened to include pregnant women up to six months postpartum and children up to age five. The program’s scope also widened to include nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to healthcare and social services, marking a shift from food distribution to a comprehensive maternal-child health intervention.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, WIC invested heavily in public awareness campaigns and community partnerships, reaching a broader share of eligible families and integrating more fully with local healthcare systems. Its effectiveness and bipartisan support have made it one of the most cost-efficient public health programs in U.S. history.

As of Fiscal Year 2024, WIC serves approximately 6.7 million participants each month, including an estimated 41 percent of all infants in the United States, with total federal expenditures of about $7.2 billion. Its sustained success underscores the critical role of early nutrition in shaping lifelong health outcomes and the value of federal nutrition programs as pillars of public health infrastructure.

Participant Demographics & Eligibility

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) was designed to serve anyone who meets income and eligibility requirements, reflecting its core principle that no one in America should go hungry. Beneficiaries include children, working families, individuals with disabilities, older adults, veterans, active-duty military members, and both employed and unemployed individuals. Food insecurity exists in every community, from rural towns to urban centers, so SNAP operates nationwide to ensure that every region has access to this critical program.

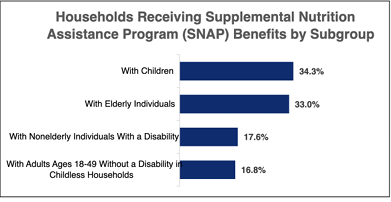

Although SNAP is universal in scope, participation skews heavily toward groups experiencing persistent economic vulnerability. Most benefits go to households with children, individuals with disabilities, and seniors, all of whom face higher risks of food insecurity and chronic disease. A large share of SNAP recipients work in low-wage service industries such as food preparation, healthcare support, retail, and manufacturing, fields that are vital to the economy yet often fail to provide stable wages or sufficient benefits. Nearly all SNAP participants live at or below the federal poverty line, which is recalculated annually to reflect inflation and living costs.

To qualify, households must meet four main federal eligibility criteria, though states have autonomy to define specific details: (1) gross monthly income must be at or below 130% of the federal poverty line, (2) net monthly income, after deductions, must be at or below 100% of the poverty line, (3) Household assets must be below a state-determined threshold, typically $2,750–$4,250, with some exceptions for households with elderly or disabled members, and (4) at least one household member must be a U.S. citizen or have eligible immigration status.

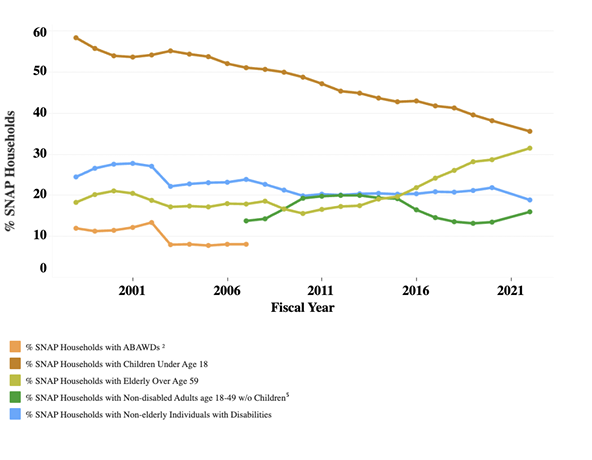

Data from the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) show distinct demographic shifts in SNAP households over the past two decades:

Households with children under 18 have consistently represented the largest share of SNAP participants, though this proportion has gradually declined from 58% in 1998 to 35.5% in 2022. This trend may reflect both declining birth rates and growing participation among other groups such as older adults and individuals without children.

Households with elderly members (over 59) increased substantially – from 18% in 1998 to over 31% in 2022 – indicating the growing need for nutrition assistance among aging populations on fixed incomes.

Non-elderly individuals with disabilities make up a steady share of participants, hovering around 20–24%, a figure that reveals SNAP’s role in supporting people unable to work due to health conditions.

Non-disabled adults aged 18–49 without children (ABAWDs) remain a smaller portion of total participants, averaging 10–15%, though the percentage rose notably during the 2008 recession and again during the COVID-19 pandemic, when work requirements were temporarily suspended.

These trends reflect broader socioeconomic and demographic changes in the U.S. including population aging, persistent income inequality, and the rising cost of living. They also illustrate how SNAP adapts to national crises: participation expanded rapidly in the wake of economic downturns (2008 and 2020) and contracted slightly as employment recovered.

WIC and SNAP together reach nearly every segment of the U.S. population that faces barriers to consistent nutrition. For instance, WIC specifically targets pregnant women, postpartum mothers, and children under five, while SNAP fills gaps for working families, seniors, and individuals with disabilities. The universality of these programs ensures that no community is left untouched, rural or urban, employed or unemployed, immigrant or native-born.

Ultimately, both programs embody a central tenet of U.S. social policy: food security as a foundation of public health and human dignity. The data reveal that participation is not a sign of failure but of systemic resilience; a collective mechanism by which society ensures that even in times of economic strain, families can access the most basic human necessity.

Program Effectiveness: What Research & Data Show

Over decades of evaluation, evidence has consistently shown that SNAP is not only a critical nutrition program but also a key driver of economic stability and public health. In federal fiscal year 2024, SNAP helped nearly 41.7 million people nationwide, roughly 12% of the U.S. population, or 1 in 8 Americans. More than 62% of participants lived in families with children, over 37% were in households with older adults or individuals with disabilities, and more than 38% were part of working families. These data illustrate that SNAP primarily supports low-income working households and vulnerable populations, ensuring access to essential nutrition for those most at risk of food insecurity.

As a public–private partnership, SNAP helps families afford a basic diet while simultaneously supporting local businesses. The majority of SNAP benefits are redeemed at supermarkets, grocery stores, and community retailers, creating a continuous flow of dollars through local economies. During the 2009 recession, for example, $50 billion in SNAP benefits generated an estimated $85 billion in total economic activity – a 70% return on federal investment – demonstrating its role as one of the most effective forms of economic stimulus during downturns. This multiplier effect is vital for low-income communities where grocery spending keeps small businesses and supply chains afloat. Beyond its economic benefits, SNAP serves as a public health intervention. Numerous studies have linked food insecurity to higher rates of chronic illness, increased use of emergency care, longer hospital visits, and lower adherence to prescribed medications, all of which drive up healthcare costs.

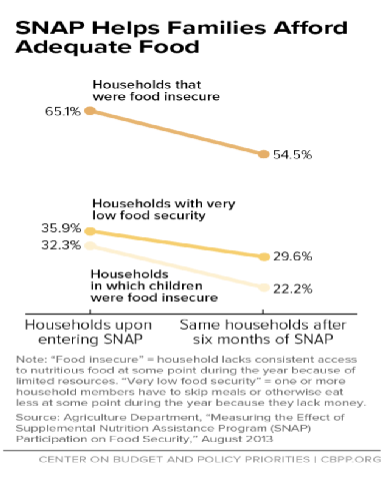

SNAP participation helps reduce food insecurity, improve nutrition, and lower long-term medical expenditures. Longitudinal data reinforces these findings. Households with varying levels of food insecurity experienced, on average, a 9% reduction in food insecurity after sustained SNAP participation. In self-reported studies, SNAP recipients consistently rated their health as better than similarly situated nonparticipants.

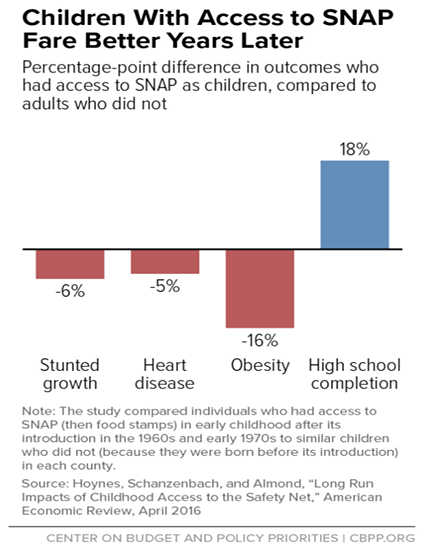

The long-term effects are particularly striking for children. A 20-year longitudinal study found that access to SNAP/WIC during pregnancy and early childhood led to better birth outcomes, lower rates of low-birth-weight infants, and improved long-term health. WIC participant data also show that 21% of infants and children with anemia achieved normal hemoglobin levels within 12 months of enrollment. Adults who had access to food stamps as children were found to have lower risks of obesity, heart disease, and stunted growth later in life. These benefits extend beyond health: improved nutrition during childhood enhances educational performance, cognitive development, and future earning potential.

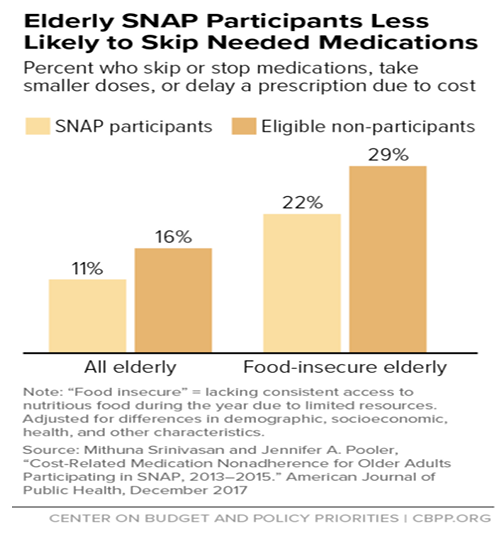

For older adults, SNAP participation is associated with nearly 10% higher medication adherence, fewer hospitalizations, and lower Medicare and Medicaid expenditures. On average, a SNAP participant incurs $1,400 less in annual healthcare costs compared to a low-income nonparticipant. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that SNAP is not just an anti-hunger initiative but a preventive health and economic policy that yields measurable returns for individuals, families, and society at large.

Similarly, decades of research confirm that WIC is one of the most cost-effective federal public health investments. Studies show that WIC participation reduces premature births and infant mortality, increases access to prenatal care, and improves maternal nutrient intake during pregnancy. WIC also promotes healthier pregnancies, stronger birth outcomes, and better early childhood nutrition, helping to ensure that children begin life with the foundation necessary for long-term growth and development.

Current Federal Developments and Their Impact on SNAP Recipients

On July 4, 2025, President Donald J. Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025 (Public Law 119-21), a reconciliation law that re-shapes tax and spending policy, including substantial changes to SNAP. The bill’s nutrition-related provisions (under Title I of the Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry Committee) impose stricter eligibility rules, shift costs onto states, and reduce benefit formulas in ways that will significantly affect recipients.

Key changes include:

Section 10101: Limits future updates to the “Thrifty Food Plan” (which sustains SNAP benefit levels) by tying increases only to the Consumer Price Index rather than a full market-basket reevaluation.

Section 10102: Expands work requirements for able-bodied adults: raising the age threshold, requiring adults with dependents to meet the same work hours as those without, and eliminating exemptions previously available to veterans, the homeless, and certain foster-care populations.

Section 10103: The allowance used by households without elderly or disabled members is removed, potentially reducing the excess-shelter deduction and lowering benefit amounts for these households.

Section 10104: Internet-connection service fees are no longer eligible as a utility cost in determining SNAP benefit size, meaning some households may see smaller allotments.

Section 10105: Starting in Fiscal Year 2028, states will be required to contribute a portion of SNAP benefit costs (from 0% up to 15%) based on their payment-error rate; currently the federal government covers 100%.

Section 10106: From Fiscal Year 2027 onward, the federal share of SNAP administrative costs will drop from 50% to 25%, meaning states will cover 75%, greatly increasing state burden.

Section 10107: The SNAP Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention Grant Program (SNAP-ED) is eliminated, removing a federal funding stream for nutrition education.

Section 10108: SNAP eligibility for certain lawfully present non-citizens (including asylum-seekers, human-trafficking survivors, and refugees) will be terminated under federal law, narrowing the beneficiary pool.

These reforms mark a major shift: SNAP will become more administratively burdensome, more tightly eligibility-restricted, more state-fund dependent, and less responsive to food-price escalation. For many recipients – especially working families, immigrants, and households in high-cost food regions – the changes will likely mean smaller benefits, greater risk of disqualification, and increased administrative hurdles.

Following the passage of the OBBB, Congress failed to reach an agreement on federal spending by the October 1, 2025 deadline, triggering a nationwide government shutdown that is still ongoing. As a result, federal agencies have not received their appropriations for October and remain unfunded for the duration of the shutdown. While some have speculated that the OBBB directly caused this gridlock, the shutdown is more accurately understood as a consequence of the intensified partisan bargaining that followed the bill’s passage. The OBBB dramatically altered federal spending priorities and programmatic rules, leading to deep divisions between Democrats and Republicans over how to reconcile these changes within the broader fiscal budget.

This prolonged shutdown has had severe implications across multiple federal agencies, most notably the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). As of late October, the USDA issued a memo announcing that federal nutrition assistance funds will not be distributed on November 1, 2025, citing the lack of congressional appropriations for the upcoming month. The Trump administration stated that it will not release contingency funds – typically reserved for emergencies – to cover Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, nor will it reimburse states that attempt to finance the benefits themselves.

According to the administration, the contingency fund was designed for unforeseen disasters, such as natural emergencies, and the current funding lapse does not meet that definition. The USDA has argued that using these funds during a shutdown would be legally impermissible, as they were not appropriated for regular program operations. This interpretation marks a significant departure from precedent, since previous administrations have used contingency reserves to maintain essential aid during temporary funding lapses, ensuring that millions of low-income families did not lose access to food assistance.

The political disagreement has fueled rising tensions in Congress, with lawmakers from both parties exchanging blame over the impending humanitarian and economic fallout. If benefits remain suspended, over 40 million people are expected to lose access to their primary source of food assistance. The majority of these recipients are children, seniors, individuals with disabilities, and low-income working families, who heavily rely on SNAP to feed themselves and their households. Experts warn that an extended disruption could erase years of progress in reducing food insecurity, increase reliance on food banks already at capacity, and exacerbate health disparities among the nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Response: State Action, Community Programs and Mitigation

Each state has responded differently to the unfolding SNAP crisis. Some are using emergency funds to keep benefits flowing, while others are directing residents to food banks, pantries, and local charities for assistance. Governors across the country have issued urgent warnings to SNAP recipients and taken varied actions to cushion the impact of halted federal aid.

Several states have mobilized direct relief efforts. California Governor Gavin Newsom announced $80 million in state funds for local food banks and deployed the National Guard to assist with food distribution – critical measures in a state that serves over five million SNAP participants. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz approved $4 million for emergency food aid, while New York committed funding for over 16 million meals statewide. Virginia pledged to sustain SNAP coverage through the duration of the shutdown, and Louisiana plans to maintain assistance until November 4. New Mexico allocated $8 million, and Colorado dedicated $10 million to support local food networks.

In contrast, many other states have not yet announced specific funding plans, instead relying on community organizations and volunteer networks to fill the gap. Food banks nationwide are preparing for unprecedented demand. Meanwhile, private companies have begun stepping in: for instance, DoorDash has launched an emergency response initiative to support food distribution, pledging to waive merchant fees for food banks and community organizations, an effort estimated to facilitate over one million meals next month.

In Georgia, where roughly 1.6 million residents – including children, older adults, and individuals with chronic conditions such as stroke survivors – depend on SNAP, officials have announced that benefits will pause on November 1 because federal funds have not been appropriated. The Georgia Department of Human Services notified recipients that no new benefits will be issued until Congress restores funding, although existing EBT balances remain usable. State leaders have acknowledged that Georgia does not have the financial capacity to replace the lost federal funding, leaving the program effectively frozen. Meanwhile, food banks such as the Atlanta Community Food Bank and Hosea Helps warn they are already nearing capacity, with small grocers and rural retailers bracing for significant revenue losses as SNAP dollars are expected to disappear from local economies.

Amid the uncertainty surrounding federal funding, advocates have released practical guidance to help SNAP recipients navigate the crisis and access alternative resources. Drawing from recommendations by “Call Your Senate” and other national anti-hunger organizations, the following steps outline how individuals and families can act during the shutdown:

Contact 211 for Local Assistance Dial 2-1-1 or visit 211.org to locate nearby food pantries, hot meal programs, mobile food distributions, and emergency community resources.

Find Local Food Banks and Charities Near You The Feeding America network may be of use – visit the Feeding America Food Bank Locator website to find places near you that may offer relief. Common sources of free meals include church-based food pantries, community centers, Salvation Army locations, soup kitchens, and mobile food pantries.

Plan and Prioritize Existing Benefits If October benefits are still available, families are advised to budget cautiously, buy in bulk, prioritize shelf-stable foods, and seeking community-based meal services to stretch remaining resources.

Conclusion

The current crisis reflects more than a temporary policy dispute; it exposes the fragility of the systems that millions of Americans rely on to meet their most basic human need: food. What began as a political impasse in Washington has now rippled into every corner of the nation, threatening not only household stability but also local economies, public health, and community resilience. The government shutdown has revealed how tightly food security is interwoven with the nation’s broader social and economic health. When one link breaks, the effects cascade outward. Food banks strain to meet unprecedented demand, small grocers lose vital revenue streams, and families face impossible choices between nutrition, rent, and medicine.

Yet, amid this uncertainty, there remains a shared hope: that congressional leaders will reach an agreement to restore federal operations and resume nutrition assistance funding. The urgency of this moment cannot be overstated: every day of delay compounds the risk of hunger, malnutrition, and widening inequality. Without swift action, the United States risks undoing decades of progress in reducing food insecurity and improving health outcomes for vulnerable populations.

If resolved promptly, this crisis can serve as a pivotal reminder of the importance of maintaining and strengthening the federal safety net. SNAP and WIC are not mere welfare programs, they are foundational investments in public health, child development, and economic stability. A nation’s strength is measured by how it safeguards its most vulnerable members. Protecting these programs is not only a moral obligation, but a commitment to the long-term well-being, dignity, and resilience of the American people.

References

Carlson, Steven, and Joseph Llobrera. SNAP Is Linked with Improved Health Outcomes and Lower Health Care Costs, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 14 Dec. 2022, www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-health-outcomes-and-lower-health-care-costs.

Caswell, Julie A. “History, Background, and Goals of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Define Benefit Adequacy., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 23 Apr. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK206907/.

Caswell, Julie A. “History, Background, and Goals of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Define Benefit Adequacy., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 23 Apr. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK206907/.

“Characteristics of Snap Households: Fiscal Year 2023.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/research/snap/characteristics-fy23. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“Development of a WIC Participant and Program Characteristics Longitudinal Data Set.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/pc-longitudinal-dataset. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

Freking, Kevin. “Trump Administration Won’t Tap Contingency Fund to Keep Food Aid Flowing, Memo Says.” AP News, AP News, 25 Oct. 2025, apnews.com/article/snap-food-assistance-government-shutdown-9cece00f9d6ef39fc5a0240ca2374696.

“Georgia: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 21 Jan. 2025.

Higham, Aliss. “SNAP Benefit Map Shows States Offering Help as Funding Expires.” Newsweek, Newsweek, 28 Oct. 2025, www.newsweek.com/snap-benefit-map-shows-states-offering-help-as-funding-expires-10949583.

“Interactive: Workers from a Wide Array of Occupations Use Snap | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/workers-from-a-wide-array-of-occupations-use-snap.

“Interactive: Workers from a Wide Array of Occupations Use Snap | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/workers-from-a-wide-array-of-occupations-use-snap.

Lillis, Mike. Food Stamp SNAP Funding Expiration Set to Impact 40 Million Americans as Shutdown Hits One Month Mark, The Hill, 26 Oct. 2025, thehill.com/homenews/house/5572490-usda-snap-funding-impasse/.

Martichoux, Alix. Federal Snap Benefits Won’t Be Paid in November: What Happens Next?, The Hill, 27 Oct. 2025, thehill.com/homenews/5574835-federal-snap-benefits-wont-be-paid-in-november-what-happens-next/.

Martichoux, Alix. SNAP Benefits May Run out Nov. 1. Here’s How You Could Still Get Food Assistance, The Hill, 23 Oct. 2025, thehill.com/homenews/nexstar_media_wire/5569987-snap-benefits-may-run-out-nov-1-heres-how-you-could-still-get-food-assistance/.

Maurer, Travis. “Georgia Snap Benefits to Pause amid Shutdown: What Users Must Know Now.” FOX 5 Atlanta, FOX 5 Atlanta, 28 Oct. 2025, www.fox5atlanta.com/news/snap-benefits-georgia-government-shutdown-november-pausing.

“A Quick Guide to Snap Eligibility and Benefits.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

Rego, Max. “Doordash Vows Aid as Snap Food Stamp Benefits End.” Doordash Offers Emergency Response to SNAP Crisis, The Hill, 27 Oct. 2025, thehill.com/business/5574857-doordash-waives-fees-snap-government-shutdown/.

Roberts, Steven V. Food Stamps Program: How It Grew and How Reagan Wants to Cut It Back; the Budget Targets (Published 1981), The New York Times, 4 Apr. 1981, www.nytimes.com/1981/04/04/us/food-stamps-program-it-grew-reagan-wants-cut-it-back-budget-targets.html.

“A Short History of SNAP.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/snap/history Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

SNAP Benefits at Risk as Shutdown Persists: What to Know, The Hill, 23 Oct. 2025, thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/5570223-snap-benefits-at-risk-government-shutdown/.

“SNAP Benefits Crisis: What’s Happening & How to Get Help.” Contact Your US Senator, 23 Oct. 2025, www.callyoursenate.com/snap-benefits-crisis-whats-happening-how-to-get-help/.

“Snap Household Characteristics Dashboard.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/data-research/data-visualization/snap/household-characteristics. Accessed 28 Oct. 2025.

“Snap, Explained.” Move For Hunger, moveforhunger.org/snap-explained Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“SNAP: State by State Data, Fact Sheets, and Resources.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities , www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-state-by-state-data-fact-sheets-and-resources. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025 – ABAWD Waivers - Implementation Memorandum.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/snap/obbb-ABAWD-Waivers-Implementation-Memo. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

Sutherland, Callum. “Experts Issue Grave Warning as SNAP Benefits Set to Run Out.” Time, Time, 27 Oct. 2025, time.com/7328216/snap-benefits-food-stamps-halting-november-government-shutdown-impact/. “Text - H.R.1 - 119th Congress (2025-2026): One Big Beautiful Bill Act | Congress.Gov | Library of Congress.” Congress.Gov, www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1/text. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“Trump Administration Says It Won’t Tap Emergency Funds to Pay Food Aid.” Politico, www.politico.com/news/2025/10/24/snap-food-aid-shutdown-usda-00622690. Accessed 28 Oct. 2025.

“USDA Food and Nutrition Service.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“What Can I Buy with Snap?” Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, www.ncoa.org/article/what-can-you-buy-with-snap/. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.

“WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2: Ninth Year Report.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/itfps2/ninth-year.Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“WIC Program Overview and History.” National WIC Association, www.nwica.org/overview-and-history. Accessed 26 Oct. 2025.